The Web’s Most Maniacal Bargain Hunters

Hardcore Amazon sellers scour stores for ‘Frozen’ dolls and cans of pumpkin—aided by apps to calculate costs

by Greg Bensinger – WSJ

April 9, 2015

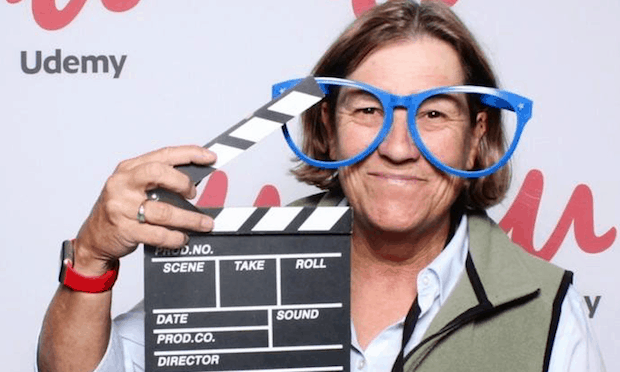

A few times each month, Anne Zarraonandia drives from her Mill Valley, Calif., office to a nearby retailer such as Walgreens or Toys ’R’ Us to scout for bargains. Armed with a price-checking app on her iPhone, she trawls the aisles, filling her cart with toys, electronics, sporting goods and packaged food.

Ms. Zarraonandia, 58 years old, isn’t looking to save a few bucks for her family. Rather, she’s looking for items she can resell on Amazon.com Inc. —at a profit.

Traditional retailers fret about the practice they call “showrooming,” where smartphone-toting shoppers scan bar codes in their stores, then seek better deals online. Ms. Zarraonandia, and thousands of others like her, engage in what might be called “reverse showrooming,” looking for goods that are cheaper in stores than online.

Industry insiders call the practice retail arbitrage. It’s more art than science, because prices are often lower online. Tricks of the trade include scoping bargain racks, shopping on senior discount day, buying unusual sizes and anticipating high demand. Software developers offer price-checking applications that help calculate potential profit, after shipping costs and online commissions.

Ms. Zarraonandia once sold $2 canned pumpkin from Safeway for $13 each ahead of Thanksgiving, when a supplier fell behind on production. She estimates that she sells about $30,000 worth of goods annually on Amazon, generating a profit of about $12,000.

“Some people say I am taking advantage of Amazon shoppers,” said Ms. Zarraonandia. “But anyone can do this.”

Amazon declined to comment.

Another seller, Chris Green, of Rehoboth, Mass., said at his peak a few years ago he was moving about $800,000 of merchandise online annually, primarily through Amazon. He cut his teeth in retail arbitrage buying discounted tool sets from Home Depot Inc. stores. “Home Depot would buy way too much of one thing and then have to discount them—which was an opportunity for me,” said Mr. Green. Home Depot declined to comment.

Such experiences led him to create ScanPower, a price-checking app for which he says thousands of people pay at least $40 a month. To improve speed on his own shopping trips, Mr. Green uses a scanner embedded in a glove.

Another app, from ASellerTool Inc., plays a “Booyah” sound when it calculates that a scanned item can be resold for a profit.

Ms. Zarraonandia and Mr. Green are among more than two million independent merchants selling goods on Amazon. Sellers set their own prices, competing to appear in the “buy box,” the most prominent position for a given search, which typically goes to the lowest-priced such item.

These merchants account for more than 40% of Amazon’s sales by unit, the company says. Amazon doesn’t disclose revenue from outside merchants. But Gene Munster, a Piper Jaffray analyst, estimates they will account for about 12%, or $12.2 billion, of Amazon’s revenue this year, climbing to $23.3 billion by 2020.

With the narrow margins inherent to retail and consumers’ fickle tastes, of course not all third-party sellers find success on Amazon. Too, some products in Amazon warehouses never find a buyer and are either recalled by merchants or ordered to be destroyed. Ms. Zarraonandia and other sellers say they occasionally pay to have Amazon dispose of some merchandise after it sits on the shelf for at least six months, a tipping point when Amazon charges a penalty, based on an item’s size.

Advertisement Amazon charges third-party merchants a commission of 6% to 15% for most items. Many merchants also pay Amazon to store and ship their goods.

Sellers say retail arbitrage can be a painstaking process, making it difficult to grow. That’s why some choose to also sell merchandise on eBay Inc. ’s website or other online marketplaces like that of Sears Holding Corp.

ENLARGE Anne Zarraonandia once sold $2 cans of pumpkin from Safeway for $13 each ahead of Thanksgiving, when a supplier fell behind on production. Photo: Ramin Rahimian for The Wall Street Journal But for a lucky few, it is a big business. Sam Cohen, owner of DWNY LLC in Ocean, N.J., said he expects to post $10 million in revenue this year from selling on Amazon, double last year’s total.

Mr. Cohen dispatches several of his dozen or so employees to stores like Kohl’s and Kmart daily to scan products and find those that he can resell profitably on Amazon. He recently opened a sorting center to handle the volume, which also includes goods he buys from liquidators and some manufacturers.

“We have an idea what we’re looking for and a pretty good idea for what sells,” said Mr. Cohen, who estimates he stores about 500,000 items in Amazon warehouses at a given time. He said items featuring characters from Walt Disney Co. ’s “Frozen” are consistently good sellers.

Mr. Cohen said his employees occasionally are stopped by retailers’ staff members, concerned that they are clearing out inventory of a certain item. When that happens, he said he has instructed them to either walk away or to buy the merchandise in separate transactions.

One morning last month, Ms. Zarraonandia checked out of a Sausalito, Calif., Ross Stores Inc. outlet with $157 in merchandise, including an Angry Birds toy set, a Jeep brand stroller bag and two Bluetooth-enabled tablet-computer keyboards.

Back at her office, in the rear of an architecture firm, Ms. Zarraonandia began removing price labels, a painstaking process requiring a jury-rigged hair dryer, a toothbrush-sized hand tool called a Scotty Peeler and a solvent for removing the last bits of glue.

She then set prices, beginning with a pink camouflage Nike iPhone 5 case for which she had paid $7.99. Amazon’s buy box showed a price of $22.97, which Ms. Zarraonandia matched. Other sellers showed lower prices, but they didn’t offer free shipping, as she did.

Seeing no competition for a car-window shade she bought for $2.99, she listed the item at $14.99. The Bluetooth keyboards, bought for $14.99 each, are listed at $35.99.

Amazon’s software tells her where to send the items, based on an algorithm that projects demand; two identical swim caps were routed to different warehouses in New Jersey and Phoenix. “You’re always hoping for Phoenix,” said Ms. Zarraonandia. “It’s closer, meaning my items are processed and listed sooner and the postage is cheaper.”

On this day, Ms. Zarraonandia shipped three boxes to Amazon warehouses near Phoenix, Newark, N.J., and Columbia, S.C. She paid UPS $20.05.

Including a few items she’d collected elsewhere, Ms. Zarraonandia calculated she’d get a check for $451—excluding her costs, like shipping, warehousing and the goods themselves—if all the items sell for their initial listing price. “That’s not a bad day,” she said.

Write to Greg Bensinger at greg.bensinger@wsj.com